Afrikahaus

Afrikahaus, Hamburg. © 2022 Bedour Braker

I am marked by the colour of my skin

The bullets are discrete and designed to kill slowly.

They are aiming at my children. These are facts. Let me show you my own wounds

my stumbling mind

my ‘excuse me’ tongue, and this nagging preoccupation!

- by Lorna Dee Cervantes

One afternoon I received a phone call from my husband telling me that we have an appointment to check out a new possible space for our office. We are both architects, and we were expanding, so we needed a bigger space in Hamburg. We met in the city centre that day and walked together to the office building where the new ‘potential’ space is located. It was a moment of mixed emotions for me! Because at that moment I did not really see a building! What I saw was a big green statue of an African worrier with a spear in one hand and a shield in the other. Standing tall with dignity as if he was guarding the main entrance. As we entered the building, we both could see a long nice and spacious courtyard that ended with another entrance, this time guarded by two gigantic elephants, in the real size! A couple of months later we moved in the new offered space, and we became part of Afrikahaus ‘occupiers’. But dare I say, the name Afrikahaus has a long history and a troubling story behind it, and its sculptures are living testimonies on it.

Afrikahaus in Hamburg

A statue of a native African man guarding the main entrance of the office building.

Photo: Bedour Braker, 2022

The colonialist & the colonized

“The colonialist and the colonized were equally chained together and trapped in a gearbox of the colonial apparatus”

Jean-Paul Sartre

One would wonder, what are those African statues doing in an office building in the middle of Hamburg? The story is actually related to the colonial era back in the seventeenth century, when European countries were chasing after trading deals at the coasts of other continents. Their deals included coffee, tea, spices, and slaves. Along the process, weapons and alcohol proved to be more appealing for payments, thus deals were cut with tribal chiefs especially in Africa (1). Except for trading posts along the coasts, the continent itself was essentially ignored for a long time (2). By the mid-19th century, Africa was considered ripe for exploration, for more trading, and for new settlements. The European contest for African colonies started to take a serious turn (1), and the different powers started to fight over more economical benefits within Africa. At that time Germany witnessed not just a rise in power but also a rise in the birth surplus, which left Chancellor Otto von Bismarck and his government with the fear of not being able to sustain the essential needs for the public (3). Although he was not in favour for colonial expansions, the pressure from the Hamburg Chamber of Commerce pushed him to finally send military enforcement to the German trading territories in Africa for protection, also to spread the German civilization among the natives (3).

"Our governments share the desire to enable the natives of Africa to join civilization."

-Otto von Bismarck

With the increasing race between the colonial powers, in 1884 Bismarck organized The Berlin Conference in Germany. Fourteen European countries in addition to the United States met to discuss the future of Africa (Austria, Hungary, Belgium, Denmark, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, The Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Norway, the USA, and Germany) while of course Africans were not invited. Behind the representatives, was a big-scale map of Africa (23).

Berlin Conference 1884-1885

Fourteen European powers met in Germany to discuss the devisions of the African continent into smaller colonies for economical benefits, which did not include the African natives themselves

Photo provided to Wikimedia commons by Allgemeine Illustrierte Zeitung, S.308; Am 28. April 2006 von Morty in die deutschsprachige Wikipedia geladen.

The initial task of the conference was to agree that mouths and basins of Congo River and Niger River would be considered neutral and open to trade for everyone. It also established a protocol for free trade stretching across the middle of Africa. The deliberations lasted from November 15, 1884, to February 26, 1885, and the European powers divided Africa among themselves into smaller pieces separated by irregular geometric borders. Those segments, which ignored the cultural and linguistic boundaries of over 1,000 indigenous regions, led to Africa as we know today (23). Germany built the third largest colonial empire after the British and French at the time. Four territories or protectorates fell under its control: (Togo and Cameroon) in the west, German Southwest Africa (today's Namibia), German East Africa (today's Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi) in the east (4) in addition to the South-sea Islands. The German’s main principle for their effective occupation was to become the catalyst for military conquest regardless of its consequences on its inhabitants (22)

The German flag

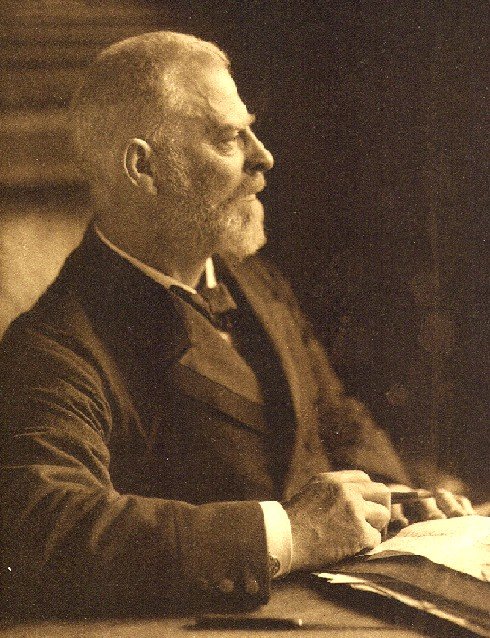

"The German flag is flying in Cameroon. Everything is fine", that was the message Adolph Woermann sent on August 17, 1884, to Chancellor Bismarck after the conference (many historians and critics claim that Adolf Woermann was the main catalyst behind the German colonization in Africa). He started to work on world’s largest privately owned shipping line after he inherited the company from his father Carl Woermann. The modern steamships and their big cargo allowed his company to intensify its transport activities along the western African coast especially in the Cameroon which became a German colony afterwards (5). The subsequent increase in trade prompted Adolf Woermann to establish both; the Hamburg shipping company and the German East Africa line (8).

The Woermann Family, and their shipping company

Eduard Woermann (1904), Adolph Woermann and Carl Woermann (1879) with ships of the Woermann Line.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons

He was the president of the Chamber of Commerce and member of the Reichstag. For years, this ambitious merchant from Hamburg was one of the main voices calling for state colonies to protect Hamburg's commercial interests on the West African coast (6). Around that time, Industrialization played a big role in making his trade a success, while Europe witnessed excessive construction of many factories. This triggered constant hunting for raw materials that were available in Africa such as copper, cotton, rubber, and palm oil were in great demand to illuminate lamps, to produce soap and as lubricant for machines (7) Another reason for enforcing colonization was the hope to control emigration. The Germans wanted to preserve the steadily rising emigration flows, especially those to America, by redirecting them into their own new territory (6). With the persistent cat-and -mouse game over the African coasts between the different powers, Woermann, fearing for his activities, sent a petition to the Hamburg Senate in 1872, and complained about the looting of his transport ships in Cameroon. As a response, warships were sent to be stationed in places where Germany made trades, and this is how the German colonialism began (already a decade before the Berlin Conference) (6).

Woermann also presented his vision of the colonial economy to the Hamburg Geographical Society, in which he explained that through plantations the products from Africa can be made available and at the German disposal in the long term (5), and in 1886 he founded his own plantation camp in West Africa colony which cultivated cocoa, coffee and tobacco. In the following years, Woermann also transported not just goods but also passengers mainly missionaries or merchants. The success of his travel/ transport company led the German empire in 1900 to sign a contract with him and since then his company was obliged to provide regular subsidized shipping service with a maximum travel time of 30 days between Hamburg and the German colonies in Southwest and East Africa.

What indigenous?! This is a German land!

It was not until the mid-1890s that a much more brutal expansion policies began over the African lands breaking all the trading treaties they had with the tribes’ leaders. Steadily, the colonial rulers came with their forms of justice, in which punishment methods included beating, chained detention and hard labour (12). Woermann, in cooperation with colonial officials and the military forces, planned to expel the inhabitants on the Cameroon River and control the intermediary trade with palm oil suppliers. “Two treasures must be exploited, the fertility of the soil and the labour force of many millions of Negroes.” Adolph Woermann.

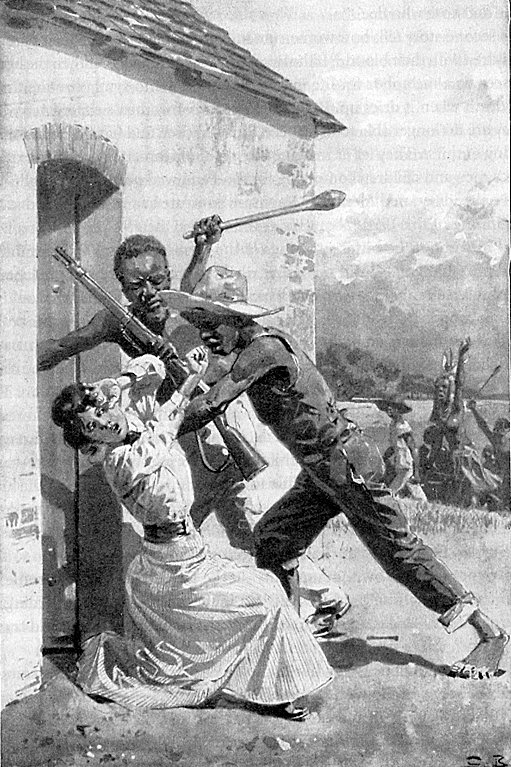

Indigenous Africans started to complain and even revolted. For them everything did not seem fair, and they were even exploited, and the trading treaties were broken by the Germans. And on January 12, 1904, the Herero and Nama tribes (from now Namibia) started their uprising and attacked the Germans. They expelled most colonists from their farms, and the staff from the railway stations. The main targets were offices of the German administration (according to German records; 119 male German civilians, 4 women and one child were killed during the events) (11). The war against the Herero and Nama tribes in South-west Africa was already preceded by twenty years of oppression. Indigenous people were considered second-class for most settlers, while only the colonizers were able to develop the country economically (10).

"Our people were shot and murdered, our women abused, and those who did so were not punished. Our chiefs consulted and decided that war could not be worse than what we suffered."

-Daniel Kariko, Herero leader 1904

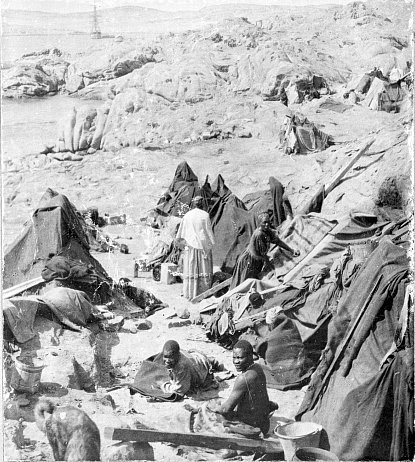

As a response, the martial control intensified even more. The German emperor commanded General Lothar von Trotha to put an end to this uprising. Trotha’s strategy led to an extensive genocide, as he perished the people in the desert while poisoning their water wells. Thousands were thirsty and countless were shot by a force of around 15,000 soldiers (Of about 80,000 Hereros, Trotha’s troops killed 64,000, and of about 20,000 Namas, he killed half and had another 2,000 imprisoned in camps) (20).

“I destroy the insurgent tribes with streams of blood and streams of money”

-Lothar von Trotha

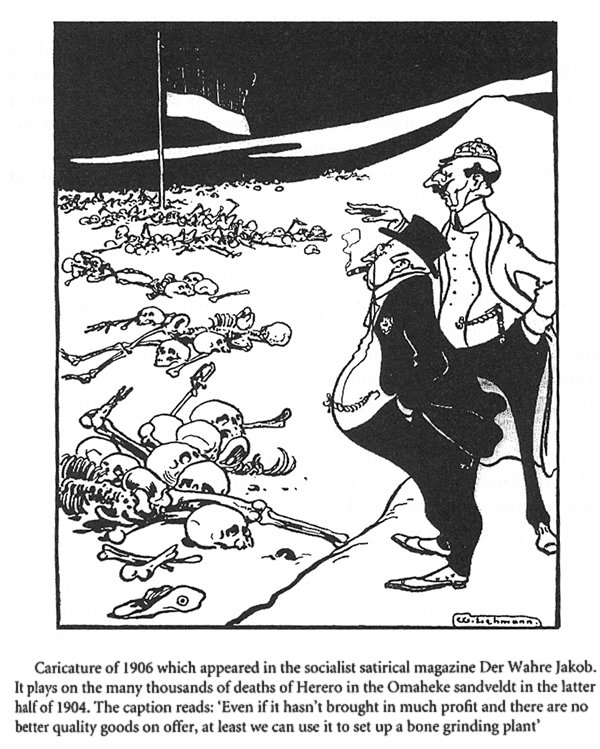

The Herero war against the Germans

Disputes between German settlers and indigenous Herero hersmen over access to land and water led to an uprising and bloody conflict known as the Herero Wars. The war culminated in a genocide of the Herero and Nama people, many of whom were driven into the desert and left to starve, with their wells poisoned.

An illustration from Le Petit Journal, 21st February 1904

Photo provided to Wikimedia commons by Der Spiegel

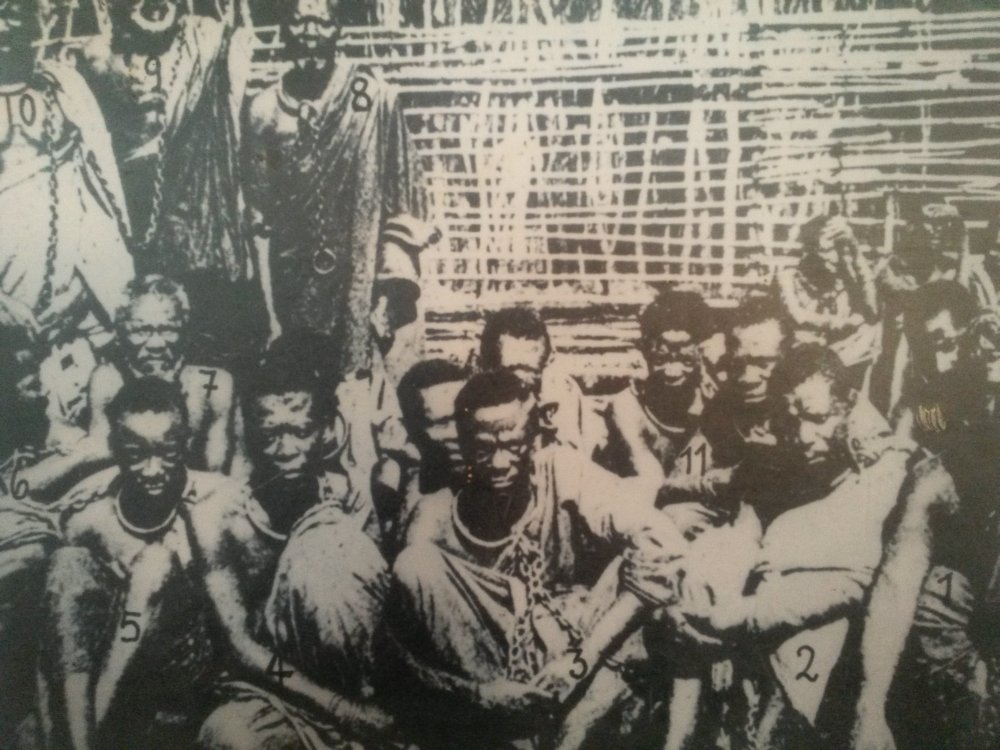

At that time, the Woermann shipping-line organized the entire supply of troops, equipment, and horses for the German 'protection force'. The remaining population of the genocide were imprisoned in camps and served German farmers and companies as a labour reservoir. Around 9000 Herero, men, women, and children, were detained in concentration camps in May 1905 (11). Men had to work for the plantations while women were forced to clean the skulls of dead men from meat residues before they were sent to Germany for medical research (11). Not to mention that Adolph Woermann’s company used those forced laborers massively for the port work and even had his own concentration camp filled with chained prisoners (5).

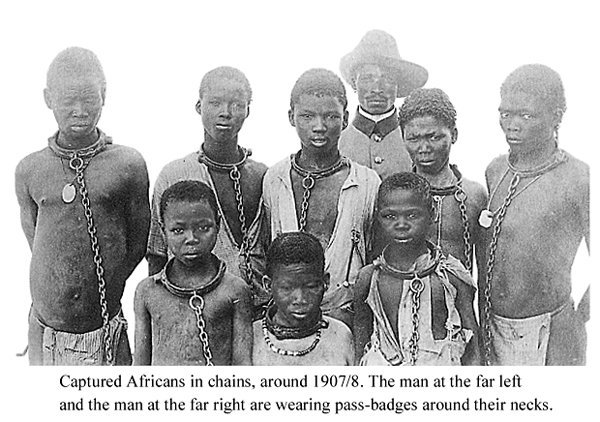

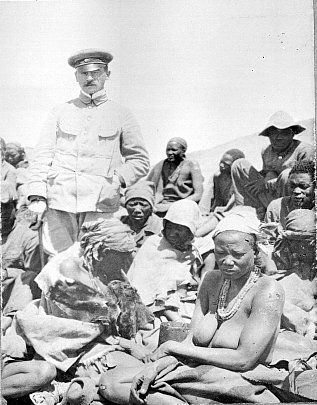

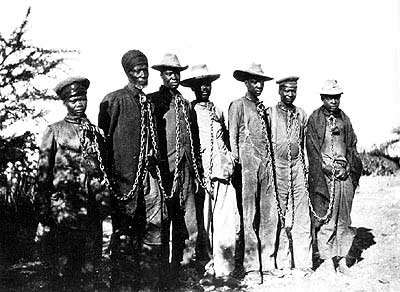

Chained prisoners

Prisoners from the Herero and Nama tribes during the 1904-1908 war against Germany.

Photo provided to Wikimedia Common by Spiegel

South-west Africa was not the only land that fell under extreme colonial measures by the Germans, and Woermann’s company was one of those who benefited from this constant subdue! In 1892, the Duala tribe in Cameroon complained to the colonial governor that the German merchants broke the Protectorate Treaty to control the intermediate rubber trade. As a result, a protection force was sent to the villages on a punitive expedition. Hundreds were chased out of their shelters into the bush, numerous opponents were shot down after a short resistance while many women and children were slaughtered (Almost every soldier brought back a head as a trophy) (6). Following this martial oppression, in 1898, Adolph Woermann founded the South Cameroon Society, which set itself the goal of exploiting the rubber resources in Cameroon. A government official from Berlin, who was traveling in the colony on behalf of the Foreign Office, explained the scene as: "…the prisoners were tied to the railing on the ship for days in the blistering heat in such a way that worms got into their bloodthirsty and swollen limbs had nested. Then, when the poor prisoners were dying, they were shot down like wild beasts...” (6)

The Namibian genocide, circa 1903

German Soldiers packing the skulls of executed Namibian at Concentration Camps.

(Skulls, bones, organs, hairs were shipped to Germany in boxes in colonial times and sent to the German scientists)

Photo via Wikimedia commons

Afrikahaus

"Should we completely prevent a large line of business from philanthropy for the Negroes, who have not been our German brothers for so long ?" -Adolf Woermann, 1885

The booming of palm oil and rubber transportations through the waters of Hamburg transformed it into Europe's largest centre for processing rubber and palm oil, this led to the need for more storage areas. A whole residential area on the Elbe was flattened to build the free-harbour with its warehouse district (Speicherstadt- now declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO) (6). Going along with that, to fund the international trading and the flourishing industry, more financial institutions were established, and the Hamburg banking centre became one of the most important in Europe (6). And to provide academic support for the flourishing business in Hamburg, a colonial institute was founded which was the nucleus of what later became the Hamburg university (6). The Woermann shipping company was in full bloom at that time and needed a proper headquarters in Hamburg to run the business. Adolf Woermann then commissioned the architect Martin Haller in 1899 to build an office building, and called it Afrikahaus (The African House). The choice of the architect was important at this point, as Martin Haller was considered one of the most influential architects in Hamburg who helped shape the cityscape of the city (He designed several office buildings, villas as well as the town hall). So the Woermann building was a sign of power and strength being designed by the most acclaimed architect for the most successful merchant on the most sought after location in Hamburg.

The main entrance of the office building with the name of its founder, Woermann, in gold on its gate.

Photo by Bedour Braker, 2022

Afrikahaus, Hamburg

Photo provided to Wikimedia commons by tps://web.archive.org/web/20161027013722/http://www.panoramio.com/photo/87172231

On a total of 7,500 square meters of rental space, the Afrikahaus is divided into a front building, two courtyard blocks and two almost life-size cast-iron elephant sculptures (9). With the statue of an African warrior, and a facade in the colours of the Woermann shipping line the building creates a visible sign of its achievements till this day (5). The company became one of the largest shipping companies in the world, with 43 steamships and “branch offices in Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Southampton, Lisbon, Las Palmas, Bathurst, Bissau, Freetown, Monrovia, Grand Bassa, Accra, Lomé, Cotonou, Lagos, Victoria, Duala and Lobito" (6). Haller chose a location close to the port and the Speicherstadt, where the goods from the colonies were stored, and became the logistical base for colonial imports as the largest in the world after London. The imported goods included human remains as well as people. The remains were sent to the scientists to be medically examined, while the living were used for constant displays at the human-zoo created by Carl Hagenbeck. It was the time when the euphoria for everything African was rising and people wanted to know more about those faraway German lands.

Afrikahaus today

The east and south wings of the building and the mosaic wall in the courtyard were partially destroyed during WWII. The canal behind the building was filled to make room for today's Willy-Brandt-Strasse . The building has been a listed building since 1972, and today it is the only building that has survived from the colonial time on Große Reichenstraße. In February 1999, various conversion were completed in a continuation of Martin Haller's ideas.

Photo by Bedour Braker, 2022

"I had the privilege of being the first to introduce the ethnographic exhibitions to the civilized world,"

-Carl Hagenbeck

Hagenbeck was originally an animal dealer from Hamburg who used the transportation ships to bring animals and humans from Africa. His concept was completely new at the time, where he put on display a complete group of ethnic people accompanied with their daily life animals as well as their dwellings and equipment. His shows were intended to give European viewers a realistic picture of the daily life of the respective ethnic groups, he called his shows Völkerschau (15).

Völkerschau tours in Europe

His shows became popular attractions in many European countries, especially between 1870 and 1940 (16). Critics nowadays claim retrospectively that the people were brought to Germany against their will, or that there were at least unfair tricks involved when recruiting them (18). The deeply embedded message of those shows made it clear to tens of thousands of Europeans, there were the Europeans who ran the business, and there was those, the others who had to risk their bodies and lives to ensure that this business of the Europeans worked. Documents show that many died, emaciated by the climate and diseases to which they had no resistance (17). Almost all of these exhibitions attracted their audiences with a clever combination of racial spectacle, erotism and a taste of anthropological science. Dances, leaps, chants, shouts, and the blood of sacrificed animals were the fundamental components of those events (19).

Senegalese village, part of the French pavilion at the Exposition Universelle of 1905 in Liège

Visitors were invited to throw coins which the Senegalese had to dive for (a practice started at the Paris exhibition of 1896).

Photo by Wikimedia commons

Then World War I happened in 1914, it was a war among empires, and its consequences are sometimes seen as a move from empire to a world of self-determining nation-states. Germany lost control of its colonial empire after its colonies were invaded by the allied forces during the first weeks of the war. And after the treaty of Versailles, each colony became a league of Nations mandate under the supervision of one of the victorious powers (12). The German colonies lasted only for thirty years from 1884 to 1919, and for a long time, German historians did not have the courage or the urge to re-question or to re-visit their own German history during the colonial times, while being mainly occupied with the atrocities of the holocaust as a dark heritage. Since the 1960s German writings on that time still fails to pay attention to a wider range of the social, economic, and political consequences on the lands that were exploited by the Germans. In 2018, the ruling coalition of the conservative CDU/CSU and Social Democrat (SPD) parties agreed to take a fresh look the Germany's colonial past. I would say since 2020, I could find many writings and articles in the German press and also scientific reports talking about those thirty years.

Does our history define who we are today?

"We in Germany have sold ourselves the illusion that we came out of the colonial times with just a few scrapes or that German colonialism was too short to create lasting damage,"

-Michelle Müntefering, the minister of state for international cultural policy.

Hamburg praises itself as a gateway to the world, but this world was created because it was a colonial world until a recent time. They traded with colonial powers, they bought, sold people and colonial goods, and they left their traces through the history; Afrikahaus with its trading past, Hagenbeck park and its human displays. Missionaries, merchants, officials, soldiers, and researchers collected not only artistic objects and tools, but also stuffed animals, human skeletons and skulls, and now the museums are filled with them (1) (around 1.5 million colonial objects are stored in the depots of German museums. They were either bartered, bought, and stolen (14) and now their own people cannot even have them back to their homeland even after pledging to the Germans in the past few years). Also, African human remains stored in the University Hospital in Hamburg, in addition to some streets and memorials honouring Germans who served in the colonies and had their extreme ways to control the indigenous population. Those are all living testimonies of Hamburg's colonial and racist past, but they are also traces that can help us understand our history and even learn from its atrocities as a dark heritage. This colonial past left its deep prints on the colonized lands, which are now politically and socially unstable and economically weak. And even when many African countries are nowadays celebrating their independence, Europe still exerts its influence on them in a much more subtle way than in the past.

Yesterday I was at the office, and I saw a group of schoolchildren with their teachers, proudly standing for a group-photo between the elephants. I kept moving my eyes between their smiling mixed-race faces and wondered, did their teachers tell them how those elephants came to Hamburg?!

Tours at Afrikahaus

Photo by Bedour Braker 2022

If you want to know more in-depth information, there is a newly released book by Spiegel (for German speakers): „Deutschland, deine Kolonien“: Geschichte und Gegenwart einer verdrängten Zeit - Ein SPIEGEL Buch, and it is highly recommended

More useful sources:

Bohr, F., Knoefel, U, Schmitter, E., 2021, Die Deutsche Blutspur im Paradies, Speigel

Gittermann, A., 2021, Steinriech durch Schnaps und Zwangsarbeit, Spiegel.

Hielscher, H., 2019, Die Tragödie um Rudolf Manga Bell, Spiegel

https://www.namibia-adventures.com/die-deutsche-woermann-linie-colonial-history/

https://web.archive.org/web/20160304054809/http://www.afrika-haus.com/historie.html

Unterberg, S., 2014, Aufräumen, aufhängen, niederknallen, Spiegel

Mühlhahn, K., 2017, The cultural legacy of German colonial rule, De Gruyter

Klußmann, U., 2021, Wie ein Sadist zum Reichskommissar in Deutsch -Ostafrika wurde, Spiegel

Dieden, A., 2020, Die gestohlene Seele: Streit um Raubkunst aus Kamerun, DW.

Kulke, U., 2014, Wilde Menschenfresser und Sexmonster im Container, Welt

Sánchez-Gómez, L., 2013, Human Zoos or Ethnic Shows? Essence and contingency in Living Ethnological Exhibitons, Culture & History Digital Journal 2(2)

https://fink.hamburg/snowball/hamburg-als-drehscheibe-des-kolonialismus/

Pelz, D., 2021, How serious is Germany taking its colonial history, dw

Gathara, P., 2019, Berlin 1884: Remembering the conference that divided Africa, Aljazeera

For more information, please click on the photos in the gallery to take you to their pages on Wikimedia commons